On a recent work trip to Abuja, I hailed a driver on a popular ridesharing app to take me from the airport to my hotel. The driver who responded was a vivacious, friendly, and well-spoken young woman. A few minutes into the ride, she asked me, “How much is the price on the app?” When I told her, she stylishly but politely told me, “ Sir, please pay it directly into my bank account. The app takes too high a percentage, and it’s not worth it.” Normally, I would argue, but it was late in the afternoon; I was tired from the flight; she was a good conversationalist, so I paid.

That experience reminded me of something I have heard from several people I know about e-hailing apps nowadays. As a friend put it, the first question the driver asks is: “Elo lo gbe wa lori app?” ( Yoruba for how much did it bring on the app?) More often than not, the driver would then demand that the passenger pay a higher price than the app into their personal bank accounts, or no dice.

When news broke that Eden Life paused its consumer-facing operations in January 2026, directing subscribers to a message about a “hiatus until further notice,” those experiences were the first things that came to mind.

The home services startup, which once epitomized the promise of tech-enabled convenience during the COVID-19 boom, had raised over $2 million and expanded to Kenya. Yet by October 2025, after what the company called a “rigorous internal audit of unit economics,” Eden Life joined a sobering list of Nigerian B2C startups that discovered a painful truth: consumer love is not enough to pay the bills.

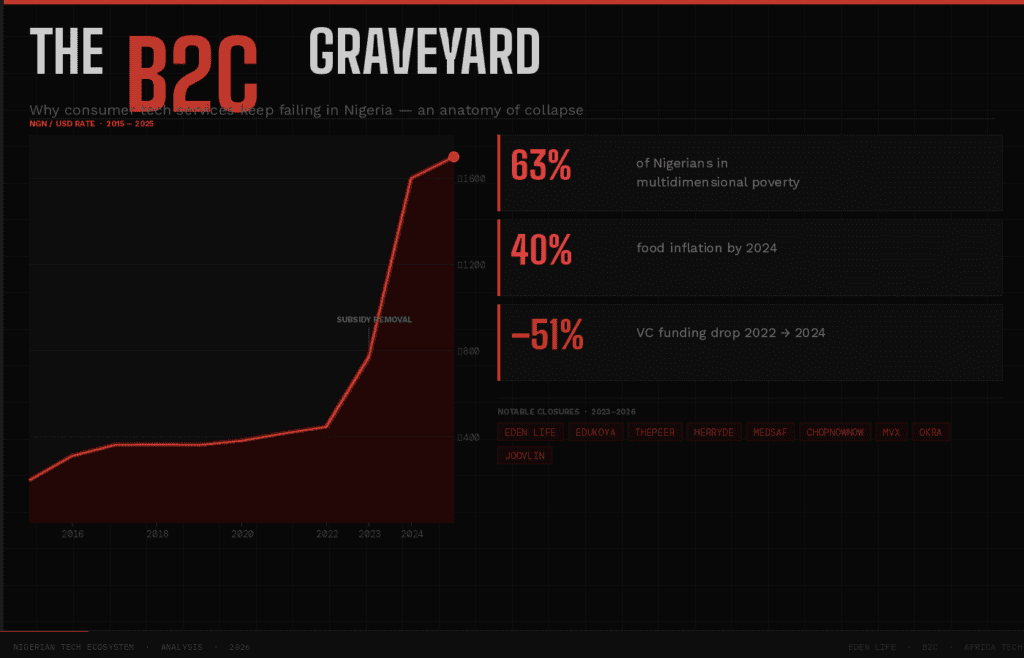

Eden Life’s retreat isn’t an isolated incident—it’s a pattern. Between 2024 and early 2026, Nigeria witnessed an unprecedented wave of B2C shutdowns. Edukoya, the edtech platform that raised $3.5 million and gained 80,000 users, closed in February 2025. Thepeer, the fintech API startup with $2.3 million in funding, shut down in April 2024. HerRyde, Chopnownow, Joovlin, and Medsaf all ceased operations despite millions in venture capital. According to Startupgraveyardafrica, nearly half of all African startup closures between 2013 and 2024 were Nigerian companies, with B2C services disproportionately represented.

The question isn’t whether Eden Life will successfully restart its consumer business. The question is why Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy and most populous nation, has become a graveyard for consumer-facing tech services.

The Vanishing Middle Class

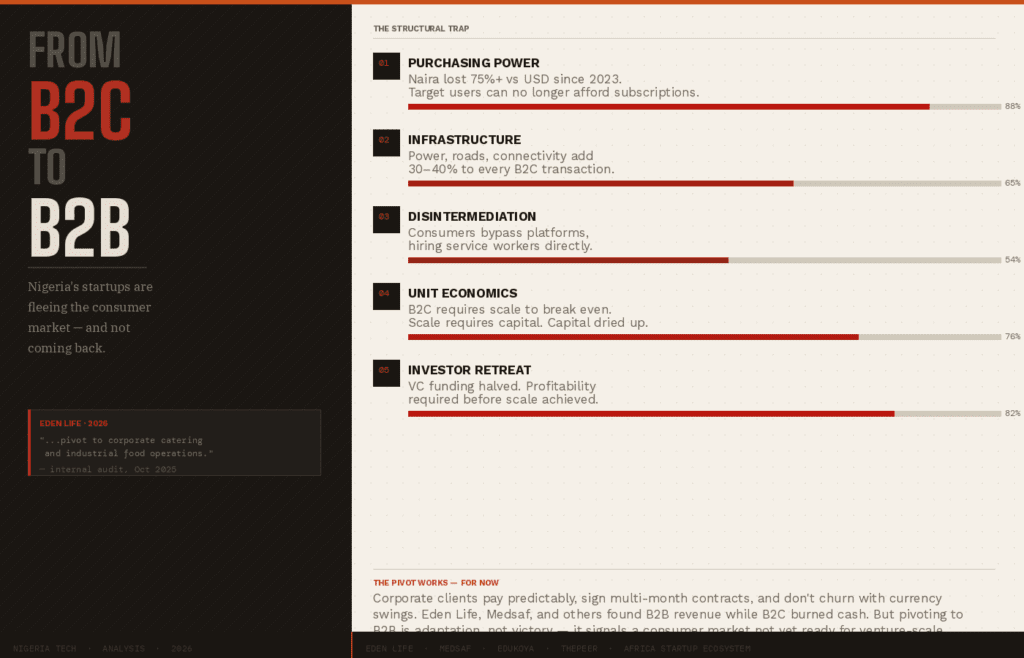

At the heart of Nigeria’s B2C crisis lies a fundamental problem: the consumer base is eroding. The naira’s collapse—from N400 to $1 in 2023 to N1,700 by late 2024—effectively halved Nigerians’ purchasing power for imported goods and services overnight. For B2C startups with dollar-denominated costs like cloud infrastructure, payment processing fees, and imported equipment, this currency crisis created an impossible squeeze.

Consider the numbers. In 2022, 78 percent of Lagosians earned less than N100,000 monthly (roughly $65 at current rates), according to PaidHR’s State of the Employed Report. By 2024, food inflation hit 40 percent, with a 50kg bag of rice—a household staple—doubling from N35,000 to over N70,000 in just two years. When families are spending more than their entire income on basic survival, premium subscriptions for meal delivery, laundry services, or educational apps become unthinkable luxuries.

Eden Life discovered this reality through painful experience. The company admitted that “the viability of individual food subscriptions was challenged by macroeconomic factors over the last 24 months.” Translation: their target customers—affluent Lagos households—were themselves downgrading, emigrating, or simply unable to justify N50,000 monthly subscriptions when groceries consumed their entire budget.

This isn’t temporary belt-tightening. The IMF forecasts Nigeria’s economy will stagnate in dollar terms through 2025, with inflation remaining above 23 percent. Multidimensional poverty, which considers income alongside access to healthcare, education, and basic services, affected 63 percent of Nigerians in 2022. The middle class—the demographic engine that powers consumer subscription services in other markets—is being systematically obliterated.

The Unit Economics Trap

But purchasing power alone doesn’t explain why well-funded startups with genuine product-market fit still fail. The deeper issue is structural: According to a study done by PlanetWeb, A digital solutions agency, B2C services in Nigeria face costs that grow faster than revenues can scale.

One can surmise from precedent that this was what happened to Eden Life’s B2C model. The company found that “industrial catering and corporate food subscriptions” were “primary growth drivers” because businesses sign predictable contracts, pay reliably, and order at scale. Replacing individual consumers with corporate clients reduces customer acquisition costs, payment friction, and logistics complexity. To put that in a layman’s language, the logistical issues involved in delivering food to 30 staff of one company, for example, are less complex than those of delivering food to individuals in 30 houses. As companies like Safeboda and Opay(with their ORide app) have learnt, B2C operations require maintaining dense networks of delivery personnel, managing hundreds of small transactions, and absorbing the friction costs of Nigeria’s infrastructure gaps.

The infrastructure deficit is punishing. Unreliable electricity forces businesses to run generators, adding 30-40 percent to operational costs. Poor roads slow deliveries and damage vehicles. Inconsistent internet disrupts payments and order management. These aren’t startup problems; they’re existential headwinds that make every delivery, every transaction, more expensive than in markets with functional infrastructure.

The Disintermediation Problem

Remember my Abuja experience that I shared at the beginning of this piece? Here is where it becomes significant. What happened to me is an example of an additional challenge specific to emerging markets: labor disintermediation. Eden Life’s model (similar to how Bolt and Uber operate) depended on abstracting away the complexity of hiring, managing, and paying domestic workers. However, a communal society like Nigeria creates a market where informal labor relationships are standard, and trust is personal. Consumers often discover they can hire the same cleaner or cook directly—and pay less without the platform taking a cut. I, for example, didn’t mind paying the nice lady driver offline, because I related with her personally (by the way, I didn’t bother going on the app again after I finished my business in Abuja, I just called the young lady, and she came to pick me up at my hotel for the same price. She even gave me her phone number to call anytime I have business in Abuja.)

This dynamic played out across sectors. When economic pressure intensified, consumers who’d grown comfortable with Eden Life’s vetted service providers simply negotiated direct arrangements, cutting out the middleman. The startup had absorbed costs of recruitment, vetting, insurance, and payment infrastructure, only to watch its suppliers establish direct relationships with customers. In tight economic times, this disintermediation accelerates as both workers and consumers seek to eliminate the platform fee.

The B2B Exodus

Tayo Oviosu, Group CEO, Paga, said something on the Afropolitan Podcast with Eche Emole and Chika Uwazie about how investors and tech founders often fall into the “200million population” trap when talking about B2C products in Nigeria. He notes that while the population of Nigeria is around 200 million people, due to poverty, limited disposable income, and infrastructure gaps, among other issues, the actual addressable market is less than 10% of that figure.

This context allows one to connect the dots. Medsaf similarly pivoted from consumer-facing pharmacy services to B2B procurement before ultimately shutting down. Many prominent edtech platforms now focus on selling to schools and employers rather than individual learners. Even consumer fintechs find that their most sustainable revenue comes from B2B infrastructure and API fees rather than end-user transactions.

The lesson here is that Nigeria’s consumer market, despite its size and youth, may not be ready to support venture-scale subscription services. The combination of purchasing power decline, infrastructure deficits, and structural costs creates an environment where selling to businesses becomes the only viable model.

What This Means

Eden Life hasn’t permanently shut down. The company says B2C reintegration is “in the very near future.” But this optimism overlooks the fundamental conditions that forced the pause. Unless inflation subsides, infrastructure improves, and purchasing power recovers, none of which looks like happening very soon. The unit economics that broke Eden Life’s consumer model will break its restart, too.

For Nigeria’s tech ecosystem, the lesson is sobering. Consumer-facing subscription services, particularly those targeting premium households with international cost structures, face existential challenges. The path forward likely involves radical localization, aggressive cost reduction, and patience that venture capital timelines don’t accommodate.

The graveyard of Nigerian B2C services contains genuinely innovative companies that built products consumers loved. Eden Life delivered excellent food. Edukoya created engaging educational content. Thepeer solved real payment friction. But in Nigeria’s current economy, consumer love isn’t enough. The services that survive will be those that solve business problems, operate on dramatically lower cost structures, or somehow serve consumers who don’t exist yet—those with stable income, reliable infrastructure, and discretionary spending power.

Until that day arrives, expect more casualties. The B2C model that works in San Francisco, California, doesn’t work in Lagos, Nigeria. And no amount of venture capital can change that fundamental reality.

No Comments