ICYMI: In Part I of this story, I explored the rise and fall of Alaba’s reign, the disruptive power of blogs, and how streaming fractured the music ecosystem. We heard from artists, execs, and producers about the new age of discovery—where algorithms replaced the all powerful traditional gatekeepers and birthed the blog and streaming eras. If you missed it, read here: From Alaba to Algorithms: How Tech Changed Nigerian Music (Part I)

Now in Part 2…

The story continues into the Age of Virality. What happens when music becomes a TikTok challenge? When AI starts producing Afrobeat? When artiste development is replaced by quick clicks and follower counts? Featuring insights from top talent managers, A&Rs, producers, and artistes, the concluding part of this story takes a deep dive into into the rise of new platforms and culture, tensions between virality and sustainability, and how the next era of Nigerian music might be shaped—not just by fans, but by code. Enjoy your read!

Nigerian Music: New Platforms, New Behaviours

The arrival of streaming didn’t just change how we listened to music—it transformed how artists rose, how trends spread, and how success was measured. From TikTok virality, playlists and dance challenges, the Nigerian music industry stepped into an era where discovery is algorithmic and careers are won—or lost—by the scroll.

The TikTok Effect

When I asked Dafe which platforms were making the biggest impact on how Nigerian artistes break out today, the answer came fast and clear.

“I’m not even going to lie to you—it’s TikTok. TikTok is where it’s at.”

The era of TikTok is not up for debate—it’s the engine driving discovery, virality, and audience building in today’s music landscape.

“TikTok has managed to bring together everything that a social media platform built to sell music should have,” he explains.

“It has the audience. It has the right kind of content. And most importantly, the people behind the platform are intentional about making content fly.”

That word—intentionality—comes up again and again.

“The algorithm? You can work with it. If you understand how it works, you can ride it.”

He breaks it down further by comparing TikTok to other platforms: TikTok is content-based. Twitter is conversation-based. Instagram is brand-based. WhatsApp/Facebook is community-based

“But we’re in the age of content,” he emphasizes. “So you start with TikTok. That’s where you push the content out and drive visibility.”

“Once the content hits, then comes Twitter, where the conversation starts. After that, audiences want to know the artist—cue Instagram, where they connect with your brand and lifestyle. And when they’re invested enough, they move to WhatsApp or Facebook, for more intimate community building—mailing lists, fan groups, direct engagement. So those four platforms matter. But TikTok? TikTok is the first, the most important, and the most impactful for us.”

With this recognition of TikTok comes the propensity to make music specifically for the platform, a trend which created the virality vs sustainability debate.

Blowing Up vs Steady Development; Virality vs. Sustainability

When the conversation shifts to virality and longevity, there’s a common assumption that the two are at odds with each other—that one must come at the expense of the other. But Fanii sees things differently.

“I don’t think these are two things that should be pitted against each other,” she says. “Even the artists who are in it for the long run—they still want virality.”

Fanii adds that the desire to “blow” is universal. Everyone wants that moment when a song catches fire and spreads like wildfire. But she’s quick to point out a critical flaw in how some artists pursue it:

“The issue is, some people try to skip the necessary steps. They jump over artiste development. They skip the grind. They’re not putting in time on the small stages, building their chops, earning their stripes.”

Virality can give you a flash of fame, but without the foundation. Without the slow, deliberate work of building stage presence, audience loyalty, and artistic range—that moment is likely to fade away almost as soon as it appeared.

“It’s not that virality and development or longevity cannot coexist,” she explains. “It’s that longevity needs structure, and too many people are chasing virality without building anything underneath.”

“I’m not going to call names,” she begins, “but there are artists who just come into the scene, and then you find that their first song is a feature with Davido. And artistically? They’re not there yet.”

It’s a pattern we’re seeing more and more. Newbies skipping the mentorship phase and the empty-room performances, instead catapulting their way into the limelight via a high-profile co-sign. Sure, the song trends. Sure, the numbers are amazing. But, as Fanii describes it, beneath that temporary ascent, you can often see the cracks if you look closely enough.

“The song is viral for a while because obviously Davido has clout and all of that,” Fanii says. With enough marketing spend (promo teams, TikTok influencers, and paid media), you can stretch virality. “But is it a long-lasting song? No. After four or five weeks, nobody’s talking about it anymore.”

What we’re seeing here, Fanii explains, is process skipping. A shortcut that often leads to nowhere. Because artist development, which is usually the hard, unsexy part of the journey, still matters.

In the rush for numbers and virality, artistes are missing the reps. The work that builds stagecraft, presence, and audience trust. And Fanii believes this can hurt careers in the long run.

Even for gospel artistes like Fafore Taiwo, the pressure to create for virality complicates things. In a genre grounded in spiritual messages, the push to make music for the algorithm comes with obvious trade-offs.

“If it is for the algorithm, it is enhancing creativity,” he admits. “But if it is for the spirituality and the essence of the message, people are now downplaying that part.”

In other words, the numbers game—the chase for engagement, shares, and streams—can heighten sonic experimentation, but at a cost to the core purpose. For the Christian music genre, the core is ministry. But when engagement metrics take center stage, messages can become watery, and the music becomes more technically inventive.

“People just come up with something and be like, ‘wow… we can still do it this way’ because they need to engage the people. But… the quality of the message we tend to share—the gospel of Christ—is being downplayed.”

This tension between artistry and utility, message and performance, not unique to gospel but perhaps more sharply felt there, shows how this tech-driven obsession with virality can also flatten depth in pursuit of reach.

According to Fanii, the negative obsession with virality at the expense of development is why, despite all the tech available today, she still prefers to blood her new artistes the old school way. She uses Odumodublvck and Blaqbonez as examples of artistes who already built a solid base before getting their viral moments.

“It might sound old school,” she says, “but it still works. Odumodublvck is my favorite example”.

She explains that before his breakout, before the record deals and bangers, Odumodu was working relentlessly underground.

“He posted a video on Instagram every single day,” Fanii says. “It could be a snippet, a freestyle—anything. And that told me this guy was probably recording two to three songs a day.”

He hustled hard, begged to get on shows, and performed in every Abuja bar, lounge, and club that would have him. It was unglamorous, but it built something that no TikTok trend can replicate: real, local, grassroots loyalty.

“I still use that same method,” Fanii says. “If I discover an artist in Jos, for instance, the first thing I tell them is: ‘Conquer your city first.’ Perform everywhere. Make sure people know you in your school, in your neighbourhood. Build a fan base of 500 people who’ll stream your songs 2,000 times, who’ll buy tickets to your shows.”

That small crowd, she explains, will become your foundation. So when you eventually get to Lagos, you’re not starting from zero.

“You’ll be carrying those 500 people with you. These are people who’ve watched your growth, people who care”.

It’s the same playbook Blaqbonez used back in OAU, she mentions.

“People knew him there. That was his first fan base,” she recalls. “And then we saw him hawking his music in Lagos traffic. That’s insane!”

Fanii believes no amount of digital strategy can replace that kind of drive.

“There’s no level of work your team can do that beats that. I tell artistes all the time: your career is 80% you, 20% your team. You own the keys. If you don’t drive the vehicle, it’s not going anywhere.”

Old school? Yes. But effective? Still.

Dwin The Stoic offers a nuanced view:

“I wouldn’t say blowing up early definitely hurts artiste development,” he says. “But sometimes, it does.”

For Dwin, who is not only an artiste but also heads the team at St. Claire that’s focused on development, the problem isn’t the virality itself—it’s what happens next.

“A viral moment should be a signal to the team to start putting proper systems in place. That’s not the time to relax.”

He points to Michael Jackson as proof that early success doesn’t have to kill development.

“Michael Jackson was a star from the time he was six. And he became one of the biggest. So technically, he blew early—the earliest you could possibly blow. But even in that, there was structured artist development happening all the way.”

Virality isn’t the enemy. But when it’s mistaken for a career, that’s when the fallout begins. For Dwin, the real win is knowing when to chase virality—and when to slow down and build something that lasts. Like Blaqbonez did after he went viral.

The Tech-Fueled Overload of Nigerian Music… and Other Problems

Tech may have changed the Nigerian music industry, but everyone I spoke with could point to at least one drawback associated with it.

Listeners Fatigue

Temz

When asked what he would change about the current relationship between music and technology, Temz—a die-hard music fan and influential voice on Nigerian music Twitter—pauses. Not for lack of an answer, but because it’s complicated.

“The first thing that came to mind was money,” he admits. “But I kept asking myself—how is that an interaction between tech and music?”

Eventualy, his frustration surfaces: there’s just too much music. Technology—by removing the traditional barriers to distribution—has made it easy for anyone with a laptop and internet access to upload a song. Every day. Every hour.

“I wouldn’t mind if there was a stipulated number of songs that can come out in a month,” Temz says, half-laughing but completely serious. “It’s too crazy. I sometimes can’t even keep up.”

His gripe isn’t with the tech itself. He’s careful to clarify that.

“If somebody misuses an equipment, you still can’t blame the equipment. But without that equipment, you wouldn’t even have that problem.”

In other words, the problem isn’t tech, it’s a problem of scale. The low bar to entry has managed to blur the line between meaningful art and algorithm-chasing clutter.

He wants balance. A pause button, so to speak.

“Half of it is getting watered down. There’s a lot of noise. But even with that noise, there are still people doing the heavy lifting—really talented guys, carrying the entire industry.”

“Let’s just take our feet off the gas and breathe. Let’s reduce the noise.”

Yinka

Temz isn’t the only one feeling overwhelmed. Yinka Aiki, another committed Nigerian music fan, echoes a more measured concern—but one that still circles back to overexposure and algorithm fatigue.

“The shuffle plays some songs too often to the point I get sick of them,” he says. “Exposure is good. But I think it’s up to the listener to moderate.”

That’s the paradox. Technology introduces listeners to new music faster than ever, but it also burns through those same songs at breakneck speed. A banger today is algorithmically rinsed and replaced by the next trend before the month is over. And while Yinka believes curation is efficient, his comment still hints at the quiet erosion of music’s staying power.

The same tools that help songs “blow” are often the ones that help us move on too quickly.

SpyceBeatz

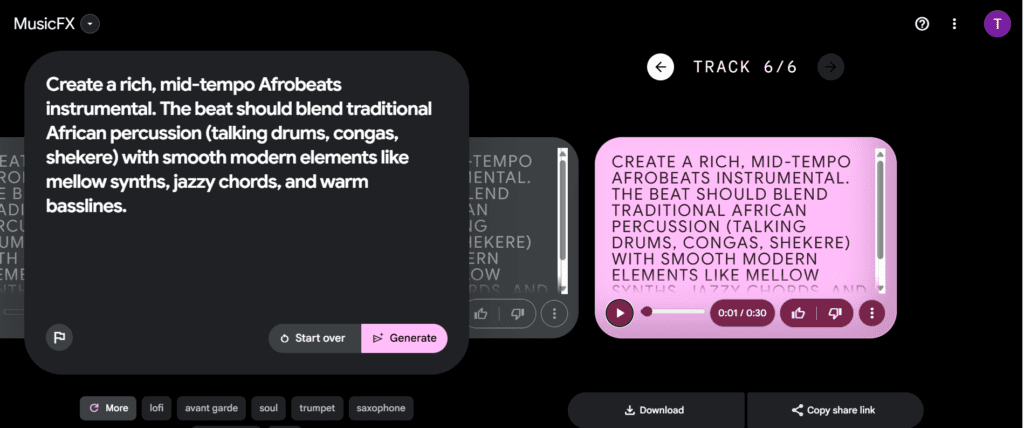

And it’s not just listeners who are feeling the pressure. On the production side, SpyceBeatz, a Nigerian music producer, has seen firsthand how tech has reshaped the game. From AI-generated samples to global remote collaborations, the possibilities are endless—but so are the challenges.

“You can literally tell an AI to create a sample for you by describing the sound, style, and mood,” he says. “It helps you work faster… but it also requires more effort to sound unique. If another producer gives the AI a similar prompt, it would give them similar sounds. Everyone starts sounding the same.”

That’s the trade-off. Speed and access have increased, but at the risk of originality flattening out. Where every producer has the same tools, and increasingly, the same prompts, the sonic palette starts to blur into sameness. Tech, in this case, doesn’t just expand creativity—it automates and potentially dilutes it.

And just like artists now write songs with TikTok hooks and challenge-worthy interludes, producers like SpyceBeatz are also forced to adapt to algorithm-shaped habits.

“I definitely consider that when making music,” he explains. “At the end of the day, music is made for the people, and if they need their attention to be pleasured before giving a listening ear, then I should try as much as possible to do that.”

In other words, attention spans are now baked into production decisions. This not only results in evolution, but it’s also being optimized, trimmed, and sometimes even compromised for platform performance.

In his own opinion, SpyceBeatz doesn’t think this shift is either entirely good or bad. But he does admit:

“I just feel that we are not really ready for some changes that we’re seeing or experiencing.”

Fanii

For Fanii, an A&R and music executive, the problem isn’t that tech itself is bad—but that it’s flattening creativity.

“Tech has made people a lot lazier,” she says. “It gives artists the sense that people will hear about them just because they run Instagram ads.”

In the streaming era, she notes, campaign templates are recycled endlessly: same influencers. Same TikTok dances, Rema-style vocals, rollout structure. That sameness, combined with shrinking attention spans, means that artists often blend into the algorithmic noise.

“There’s a big loss of creativity in the industry,” she says. “I don’t see a lot of standout moments anymore.”

Even though the numbers game rewards predictability, Fanii warns it can backfire. A recycled template that worked for one act may flop for another.

Fafore Taiwo

Gospel artiste, Fafore Taiwo, also speaks to another problem tech has introduced to Nigerian music: visibility no longer depends majorly on talent.

“In all honesty, I want to say it [the current scenario] is favouring more the people that have the know-how,” he says when I ask if talent trumps know-how. “You can have the gift, you can have the skill… but if you are not in that era with us, your gift is as good as for you and the people around you.”

In his view, tech rewards those who understand how to “game the system”—to optimize content for the right platforms, use the right tools, and ride the algorithmic wave. It’s a shift that leaves truly talented artists in the dust if they lack the digital savvy to compete.

So while tech has opened up unprecedented possibilities for Nigerian music. Remote collaborations for artistes and producers, AI tools, global reach—it has also introduced subtle pressure points: the demand to adapt, the risk of creative redundancy, and the blurring of authenticity for virality. And across the board, there’s a shared feeling that we may well be losing something vital in the rush.

Tech, The Future of Nigerian Music, and the Power of Collective Creativity

Everyone I spoke with in writing this story believes the future holds a lot for the Nigerian music industry and tech.

This Is Not The End

For Emmanuel Daraloye, this is not the end of tech’s intervention in the Nigerian music industry.

“I still believe that the streaming era won’t be the last phase of music distribution,” he says. “People are talking about NFT, fans investing directly in the music or astistes selling directly to fans and skipping DSPs. I believe there’s a lot more to happen that we don’t know of now.”

He believes artistes need to take enlightenment seriously and know more about the business of music, to be at the forefront of any incoming revolution, instead of having to tag along as usual.

“Many of them don’t know much about the industry. They should be more educated. There’s still a lot of the population that they haven’t reached.

There are hundreds of thousands of dollars waiting for these artistes to tap into. Outside the internet.

People in the rural area, which forms the largest part of the population, don’t have access to the internet now, the majority. They need to find a way to tap this crowd.”

For producers like Abimbola, the question isn’t whether an AI-driven era will arrive in Nigerian music—it’s how soon.

“Elsewhere it’s already happening,” he says. “You just tell [AI] what genre, what style of stuff you want… it can do all of that.”

Though Afro rhythms still present a challenge for some Western software—“it is the creativity of our producers that somehow they can manage to produce this stuff”—Abimbola believes it’s only a matter of time. As with everything African, he says, data and tech may arrive late, but when they land, they take over.

“I think it’s only a matter of time before [AI music] happens here too,” he concludes.

When asked what excites him most about the next five to ten years of music and tech, Dwin The Stoic doesn’t mention streaming revenue, or viral algorithms, or even AI right away. His answer starts somewhere deeper:

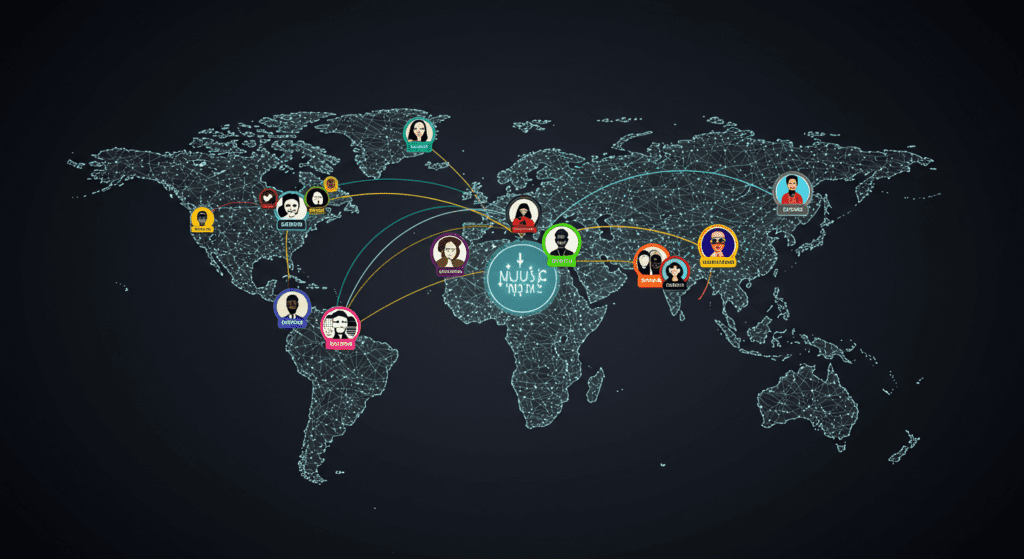

“I think what will be the biggest thing for artists is tied to the reach the internet gives us. That kind of access? It’s unprecedented.”

We Have Never Lived In A Time Like This…

For Dwin, the internet isn’t just a tool. It’s a chance for African artists to learn, unlearn, and connect beyond historical boundaries. And it’s happening fast.

“We’ve never lived in a time where I can be in my house in Lagos and know as much as I want about Korea with a few Google searches. That’s never been done before.”

This kind of borderless knowledge, he argues, has the potential to rewrite narratives long shaped by colonial distortions.

“We have a lot of work to do undoing the idea of Africa as a dark continent. A lot of that was lies. And it’s part of why we’re chasing Grammys when we don’t even have sensible awards here. We have to reframe that.”

What excites him isn’t just the reach for Nigerian music—it’s collective power. And how technology can bring us back to our roots: community, collaboration, and shared cultural value.

“You win as a collective, not as one person. That’s how Africans have always done it. And that’s where I think tech can take us.”

With tools that allow cross-border conversations, small fan bases can link across continents. Artistes in Lagos and Korea can discover each other and realize they’re not so alone.

“You with your 300 listeners here. Another person with 300 listeners there. You talk, you connect. That’s community. That’s hope.”

But with that possibility comes a warning. Africa’s lack of structure, he points out, can leave its artists vulnerable, especially in areas like AI regulation.

“When AI becomes a thing—who fights for our artists? Universal will fight for theirs. Sony will fight for theirs. But who’s fighting here? This is why we need to build structures and systems.”

Still, he’s hopeful. Even excited.

“Tech will be a huge tool for artists. It already is. But if we do the work—if we collaborate, share, protect—then what’s coming? It could be revolutionary.”

Tech Is The Present …And The Future

Fanii is a music executive and A&R, but she’s also Head of Music at TASCK. TASCK, is a creative agency founded by Nigerian rap legend MI Abaga that uses tech to help creatives elevate their brands, unlock new opportunities, and achieve lasting success. Through innovation across multiple projects, they provide the tools and support creatives need to organize, collaborate, and drive economic prosperity.

She expresses optimism about tech’s potential to ease the burdens of being a modern creative. At TASCK, she tells me, they’re working on tech solutions to simplify the “executive” side of being an artiste—project management, paperwork, contract negotiation. Tasks that usually overwhelm creatives could soon be streamlined into plug-and-play services.

“These are the kinds of gaps we’re trying to fill at TASCK. A lot of artistes, photographers, and even filmmakers struggle to be both creatives and executives,” she explains. “Tech allows us to build systems where creatives can just go to find solutions to their problems.”

She imagines a near-future where artistes no longer need to seek traditional managers, but instead subscribe to an app that handles bookings, deal sourcing, and music analysis, plugging them into relevant publishing or distribution opportunities.

“We already have systems where you can submit your music to music supervisors via certain websites and get small $5–$10 licensing deals. I see that scaling fast.”

And as new platforms continue to emerge (from TikTok’s rise to whatever comes next), Fanii is preparing to adapt:

“I’m pretty enthusiastic to see what tech has for the music industry, to be honest. I mean, we could wake up tomorrow and there’s a new platform that isn’t TikTok but does three times what TikTok does. Years ago, all we had were Instagram and Facebook.“

“As an A&R, you have to be ready to switch up instantly. I just hope I’m not too obsolete to move with the times,” she laughs.

The Music Never Stops

Recently, I passed by the same bus stop where I bought my ‘Talk About It’ album in 2008. I recognized the guy who sold it, and we exchanged greetings. He was boisterous and full of life as usual. I noticed he still had his stall, but the hustle had changed. He now sells phone accessories, while I’m looking forward to streaming M.I’s forthcoming album ‘The Wolf’ on Spotify. How the times have changed.

“My guy, nobody been dey buy CD again o”, he told me. “And man must survive na.”

I nodded in agreement. Eras will come and go, but one thing remains: everyone must find a way to survive—either by adapting to the times or pivoting entirely.

Today, a talented teen sits in a corner of his UNILAG hostel room, dreaming of going viral. Tomorrow, an AI might clone his voice. Still, he scribbles lyrics in his note app, chasing that timeless hook, one he hopes will be loved by, yet outlive algorithms. In this industry, players will come and go, but the music never stops.

Credits: Interviews with Dwin, The Stoic, Taiwo Fafore, Emmanuel Daraloye, Fanii, Dafe, SpyceBeatz, Abimbola, Temz, and Yinka Aiki, conducted by Emmanuel Essang for TechStoriex.

One reply on “From Alaba to Algorithms: How Tech Changed Nigerian Music (Part II)”

[…] (The tech revolution was just the beginning. In the second part of this article, we’ll follow its ripple effects—how it shot new platforms and channels to prominence, redefined virality, rewired artiste development, and shaped the future of Nigerian music. Read Part II here.) […]